3 Modes of exchange

Relational Exchange: Sustaining Business Through Connections

Relational exchange stands as a fundamental and arguably the most natural form of business interaction across all human societies and civilizations. Whether in bustling metropolises or quiet villages, the essence of relational exchange – conducting business through established relationships – remains a constant. A simple illustration is buying from a familiar shopkeeper in a small town, where trust and personal connection underpin the transaction.

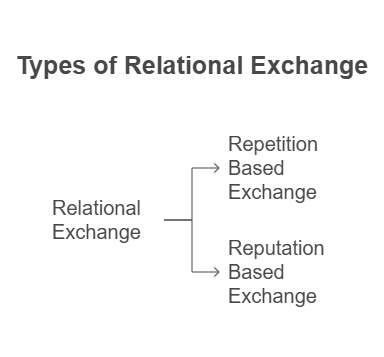

Two key mechanisms sustain these relational exchanges: repetition and reputation.

1. Repetition-Based Exchange

Description: Repetition-based exchange thrives on the principle of repeated interactions between the same individuals or entities. The anticipation of future transactions fosters a sense of mutual benefit and discourages opportunistic behavior that could jeopardize the ongoing relationship.

Key Characteristics:

- Focus on Long-Term Value: The potential for a continuous stream of income from a repeat customer outweighs any short-term gains from unethical practices.

- Disincentive for Opportunism: The risk of losing future business acts as a powerful deterrent against cutting corners or providing substandard goods or services.

- Built on Familiarity and Trust: Repeated positive interactions build trust and strengthen the relationship over time.

Example: The Genoese Trade Model

The historical trading practices of Genoa, a prominent Italian city and a long-standing center for long-distance trade, exemplify repetition-based exchange. Principals would repeatedly hire agents for lucrative ventures. Even though the principal couldn't constantly monitor the agent's actions during long voyages, the agent's incentive to remain trustworthy stemmed from the understanding that a successful and honest execution of the task would lead to future, equally profitable opportunities with the same principal. The long-term financial benefits of maintaining the relationship far outweighed the short-term temptation of absconding with the funds.

Underlying Principle: In repeated exchanges, the potential loss of future income and the benefits derived from a continued relationship serve as a powerful mechanism for ensuring ethical and quality conduct.

2. Reputation-Based Exchange

Description: Reputation-based exchange comes into play when interactions are not necessarily frequent or repetitive. In close-knit societies, an individual's or entity's reputation within the community becomes a crucial asset. The fear of damaging one's reputation and facing social and economic repercussions encourages honest and high-quality service, even in one-off transactions.

Key Characteristics:

Example: Middle Eastern and Mediterranean Mug-Rip Traders

Historically, traders in close-knit networks in the Middle East and the Mediterranean relied heavily on reputation. Principals would entrust agents with significant sums for trade ventures. While direct monitoring might be limited, the theoretical underpinning was that agents were strongly incentivized to act honestly. Any instance of cheating or providing poor service would quickly become known throughout the network, severely damaging the agent's reputation and effectively preventing them from securing future business from any principal within that community.

Underlying Principle: In close-knit societies, the potential for reputational damage and the subsequent loss of future business within the network act as a strong deterrent against opportunistic behavior, even in the absence of repeated interactions with the same individual.

The Fundamental Similarity

While repetition-based exchange relies on the prospect of ongoing interactions and reputation-based exchange hinges on the interconnectedness of a community, both mechanisms share a fundamental principle: the threat of future income restriction as a consequence of opportunistic behavior.

In repetition, this punishment comes directly from the cessation of repeat business by the aggrieved party. In reputation, the punishment is indirect but equally potent, stemming from the wider community's refusal to engage in future transactions due to a tarnished reputation.

Power-Based (Hierarchical) Exchange: Transactions Governed by Authority

While relational exchange highlights the role of connections and trust, societies are rarely purely egalitarian. Hierarchies of power have been a persistent feature throughout history, influencing how exchanges occur. Power-based exchange, also known as hierarchical exchange, is characterized by an imbalance of authority where one party can dictate the terms of the transaction and unilaterally enforce compliance.

This form of exchange is rooted in the ability of a more powerful entity to exert control over a less powerful one. Historically, feudal systems provide a stark example. Peasants, bound to the land, were obligated to cultivate crops and surrender a portion of their produce to landlords or rulers. This wasn't a voluntary exchange based on mutual benefit alone; it was driven by the landlord's or ruler's power and the peasant's subordinate position.

Examples of Power-Based Exchange:

- Feudal Systems: The relationship between a lord and a peasant, where the peasant was compelled to provide labor and a share of their harvest in exchange for protection or the right to cultivate land, exemplifies power-based exchange. The lord held significant authority and could enforce these obligations.

- Mahatma Gandhi's Champaran Movement: The exploitation of farmers in Champaran, Bihar, who were forced by British indigo planters to cultivate indigo against their will, is a clear illustration of power-based exchange. The planters wielded economic and political power to dictate production, regardless of the farmers' desires or economic interests.

- State-Controlled Economies: In economies with significant state-owned enterprises, the government can directly produce goods and services and allocate resources without primarily relying on relational or contractual exchanges. The state's authority dictates production and distribution.

- Employer-Employee Relationships: The relationship between an employer and an employee is a contemporary example of power-based exchange. While governed by labor laws and contracts, the employer generally holds the power to direct the employee's work and can terminate employment for non-compliance.

Key Characteristics of Power-Based Exchange:

- Asymmetrical Power Dynamics: One party possesses significantly more authority or control than the other.

- Unilateral Enforcement: The powerful party can impose sanctions or punishments for non-compliance without necessarily needing mutual agreement or repeated interaction.

- Lack of Voluntary Participation (Often): The less powerful party may be compelled to participate in the exchange due to their subordinate position or lack of alternatives.

- Not Necessarily Dependent on Relationships or Reputation: The exchange is primarily driven by the power dynamic, not necessarily by pre-existing relationships or the need to maintain a positive reputation with the weaker party.

How Power Influences Exchange:

In power-based exchange, if the less powerful party deviates from the directives of the more powerful one, the latter can unilaterally impose penalties. In the employer-employee scenario, failure to follow instructions can lead to disciplinary action, including termination. In historical feudal systems, disobedience could result in fines, loss of land, or even physical punishment.

Ubiquity of Power-Based Exchange:

Power dynamics are pervasive in human societies, making power-based exchange a ubiquitous phenomenon. From the hierarchical structures within organizations to the authority of governments, power influences countless interactions and transactions. Whenever one entity has the capacity to direct the actions of another and impose consequences for non-compliance, the principles of power-based exchange are at play.

In contrast to relational exchange, which relies on mutual benefit, trust, and the potential loss of future interactions or reputation, power-based exchange is fundamentally driven by the ability of one party to exert control and enforce their will upon another.

Contractual Exchange: Transactions Governed by Formal Agreements and Third-Party Enforcement

The fundamental principle of contractual exchange lies in the existence of an enforceable agreement. When a producer provides a good or service and fails to meet the agreed-upon terms (e.g., delivers substandard quality or fails to pay), the aggrieved party can appeal to a contract enforcer.

What is a Contract Enforcer?

A contract enforcer is a neutral third party with the authority to interpret and enforce contracts, and to punish parties who act opportunistically or fail to uphold their contractual obligations. This enforcer can take various forms:

- Courts of Law: The judicial system provides a formal mechanism for resolving contractual disputes and awarding remedies.

- Consumer Forums: Specialized bodies designed to address grievances related to consumer transactions and protect consumer rights.

- Police: In certain cases, particularly those involving fraud or criminal breach of contract, the police may act as enforcers.

- Arbitration and Mediation Services: Alternative dispute resolution mechanisms that provide a less formal way to resolve contractual conflicts.

By providing a mechanism for redressal, contract enforcers create a framework of accountability that underpins contractual exchange. Knowing that non-compliance can lead to legal or regulatory consequences incentivizes parties to adhere to the terms of their agreements.

Key Characteristics of Contractual Exchange:

- Formal Agreements: Transactions are governed by explicit contracts outlining the obligations of each party, including specifications, quality standards, payment terms, and delivery schedules.

- Third-Party Enforcement: A neutral entity (the contract enforcer) exists to resolve disputes and ensure compliance with the contract.

- Transactions Between Unknown Parties: Facilitates business dealings between individuals or entities without pre-existing relationships or reliance on reputation within a close-knit community.

- Emphasis on Legal and Regulatory Frameworks: Operates within a system of laws and regulations that define contractual obligations and the powers of enforcement bodies.

The Crucial Role of the Third Party:

A defining feature of contractual exchange is the presence of a largely invisible but essential third party – often embodied by the state in its various forms (government, courts, police, regulatory bodies). This third party provides the crucial function of enforcing agreements and ensuring a degree of fairness in transactions between potentially self-interested parties.

The Necessity of a Fair Third Party:

The effectiveness and widespread adoption of contractual exchange hinge on the perceived fairness and impartiality of the third-party enforcer. If the enforcement mechanism is biased or corrupt, favoring one party over another, trust in the contractual system erodes. In such scenarios, individuals and businesses may be less inclined to engage in contractual exchanges and may instead prefer to rely on relational exchanges (where trust and reputation within a network offer some protection) or power-based exchanges (where compliance is enforced through authority).