Embeddedness

Embeddedness of Economic Exchange in Social Structures

While modern economies heavily rely on contractual exchange facilitated by formal institutions, this has not always been the case. For the vast majority of human history, and even today to a significant extent, economic exchange has been deeply embedded within the existing social structure. This means that how people conduct business is intricately linked to the networks and hierarchies that constitute their society.

Before the widespread development of robust legal and contractual enforcement mechanisms, societies primarily relied on relational and power-based modes of doing business. Economic transactions were not abstract interactions between anonymous individuals but were instead woven into the fabric of social relationships and power dynamics.

Social Structures: Networks and Hierarchies

- Networks: These are webs of interpersonal connections, including family, friends, colleagues, and community members. These networks facilitate relational exchange based on repeated interactions and reputation.

- Hierarchies: These are systems of ranking and authority, such as those found in workplaces (boss-subordinate), political systems (rulers-subjects), and traditional social organizations (landlords-tenants). These hierarchies underpin power-based exchange.

The interplay between these networks and hierarchies creates the social context within which economic exchange occurs.

Economic Exchange Embedded in Social Structure

The concept of embeddedness highlights that economic activities are not isolated but are shaped by and influence social relationships and structures. In pre-modern societies, and to a considerable degree even today, economic exchange leverages these social frameworks:

- Networks for Relational Exchange: Individuals utilize their networks to engage in repeated exchanges with trusted members or rely on the reputation of individuals within the network for less frequent transactions.

- Hierarchies for Power-Based Exchange: Power structures dictate the flow of goods, services, and resources, with those in positions of authority often able to command the labor or production of those lower in the hierarchy.

Therefore, economic exchange is not simply a matter of supply and demand but is deeply intertwined with social norms, obligations, and power dynamics within networks and hierarchies.

Embeddedness Across Civilizations: Examples

The embeddedness of economic exchange is a universal phenomenon, manifesting in different forms across various civilizations:

1. China:

- Clans (Guanxi): Traditional Chinese society heavily relied on kinship-based clans and personal connections (guanxi) for conducting business. Relational exchange within these networks, based on trust and mutual obligation, was a primary mode of economic activity.

- The State: The Chinese state has historically played a significant role as a major producer and provider of goods and services through state-owned enterprises. This represents a form of power-based exchange where the state's authority dictates economic activity.

2. Europe:

- Guild System: During the medieval period, guilds – associations of craftspeople or merchants in a particular trade – regulated production, quality, and trade within their respective occupations. This represented a network-based system where members engaged in business with each other and adhered to shared standards.

- Feudal System: The feudal system was a hierarchical structure where peasants were obligated to provide labor and a portion of their agricultural output to the nobility, who held power over the land. This is a clear example of power-based exchange.

3. India:

- Jati (Caste System): The traditional Indian caste system involved Jatis, which were often kinship-based and occupational groups. Economic activities were frequently organized within these communities, representing network-based relational exchange.

- Varna (Social Hierarchy): The broader Varna system represented a social hierarchy where different communities held varying social and economic status. This hierarchical structure influenced economic conduct and opportunities, reflecting power dynamics.

The Persistence and Limitations of Embeddedness in Business

The fact that relational and power-based exchange, operating through social structures, have persisted for millennia while modern contractual exchange is a relatively recent development (3-400 years) raises a fundamental question: why are social structures so enduring in the realm of business? Even today, in regions with less developed contractual institutions, relational and power-based modes remain dominant.

To understand this persistence, consider a thought experiment: given the choice between conducting an exchange within your social structure (with known individuals from your clan, guild, caste, or feudal system) or with a complete stranger, under what conditions would you opt for the unknown?

The primary reason for the enduring power of social structure in business lies in its ability to mitigate two fundamental market frictions that arise when dealing with strangers: information asymmetry and moral hazard.

The Benefits of Embeddedness: Resolving Market Frictions

1. Information Asymmetry:

- Problem: When dealing with strangers, you lack sufficient information about their reliability, the quality of their products or services, and their past behavior. This opacity creates uncertainty and risk.

- Solution through Embeddedness: Within a social structure, individuals have a history of interactions and shared knowledge. Reputation spreads through the network, and repeated interactions provide direct experience. This familiarity reduces information asymmetry, allowing for more confident transactions. You have a better sense of who to trust and the quality they are likely to provide.

2. Moral Hazard:

- Problem: Even with some information, there's always the risk that a trading partner might act opportunistically after a transaction is agreed upon (e.g., providing lower quality than promised). Controlling the behavior of strangers is difficult.

- Solution through Embeddedness: Social structures offer mechanisms for enforcing reliable behavior. Repeated interactions create the leverage of future business. Reputation within the network can be damaged by opportunistic actions, leading to social sanctions and exclusion from future exchanges. You have the ability to exert influence and impose consequences on those within your social circle.

In essence, embeddedness provides a built-in system of trust, information sharing, and enforcement that can partially substitute for formal contractual institutions.

The Limitations of Embeddedness

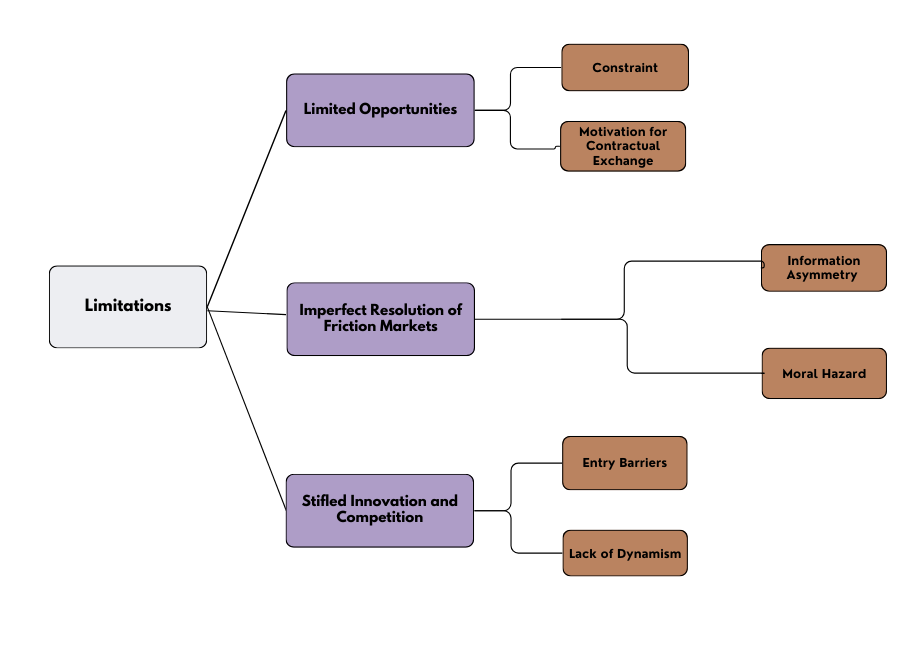

Despite its benefits, relying solely on social structure for business exchange has significant limitations, which explain the eventual rise and dominance of contractual exchange:

1. Limited Opportunities:

2. Imperfect Resolution of Market Frictions:

- Information Asymmetry - Echo Chambers: While embeddedness provides more information, close-knit societies can become "echo chambers" where the same information circulates repeatedly, potentially limiting exposure to new ideas, innovations, and diverse perspectives. Ronald Burt's research suggests that being connected to diverse groups within a network can be more beneficial for accessing novel information.

- Moral Hazard - Fragility of Reputation: Emily Kaden's work highlights the vulnerability of reputation-based systems. Gossip and malicious rumors can easily damage a good reputation, even unfairly. Furthermore, individuals with questionable behavior can sometimes still thrive within social structures. The ability to sanction opportunistic behavior within a network also has its limits.

3. Stifled Innovation and Competition:

- Entry Barriers: Close-knit groups and networks often develop mechanisms to exclude newcomers, limiting competition and innovation. Existing members benefit from reduced competition, but this can hinder overall economic progress and prevent outsiders with better offerings from entering the market.

- Lack of Dynamism: Over-reliance on established relationships and traditional practices within a social structure can stifle innovation and prevent the adoption of more efficient methods or superior products from outside the network.