Social Structure

The Divergence of Wealth: Modern vs. Traditional Economies and the Malthusian Trap

The Stark Differences in Modern Living Standards

- Global Inequality: The modern economy is marked by significant differences in the standards of living across the globe.

- Wealthy Nations: Countries like the United States exhibit high average incomes and a generally high quality of life.

- Developing Nations: In contrast, regions in India and Sub-Saharan Africa face lower income levels and higher rates of poverty.

The Relative Homogeneity of the Traditional World

- Stagnant Per Capita Income: In the traditional world (before around 1500), the average income per person globally was largely stagnant over long periods.

- Similar Living Standards Across Regions: While not perfectly uniform, the overall standard of living was relatively similar across different countries.

- Nuances in Socio-Economic Conditions: The speaker acknowledges that some regional variations existed. For example, India's climate, spices, and sugar production might have contributed to a slightly better quality of life compared to other regions.

- Comparable Basic Indicators: However, key indicators like infant mortality rates were often comparable across different parts of the world.

- Limited Income Disparity: While income levels (in terms of purchasing power for basic goods like grains) might have varied by a factor of two or three between regions, they were nowhere near the 50 or 60-fold differences seen in the modern world.

- Urban Economic Dynamism: Cities in the traditional world often exhibited greater economic activity and potentially higher income levels due to industry and trade.

The Malthusian Trap: Explaining Traditional Economic Stagnation

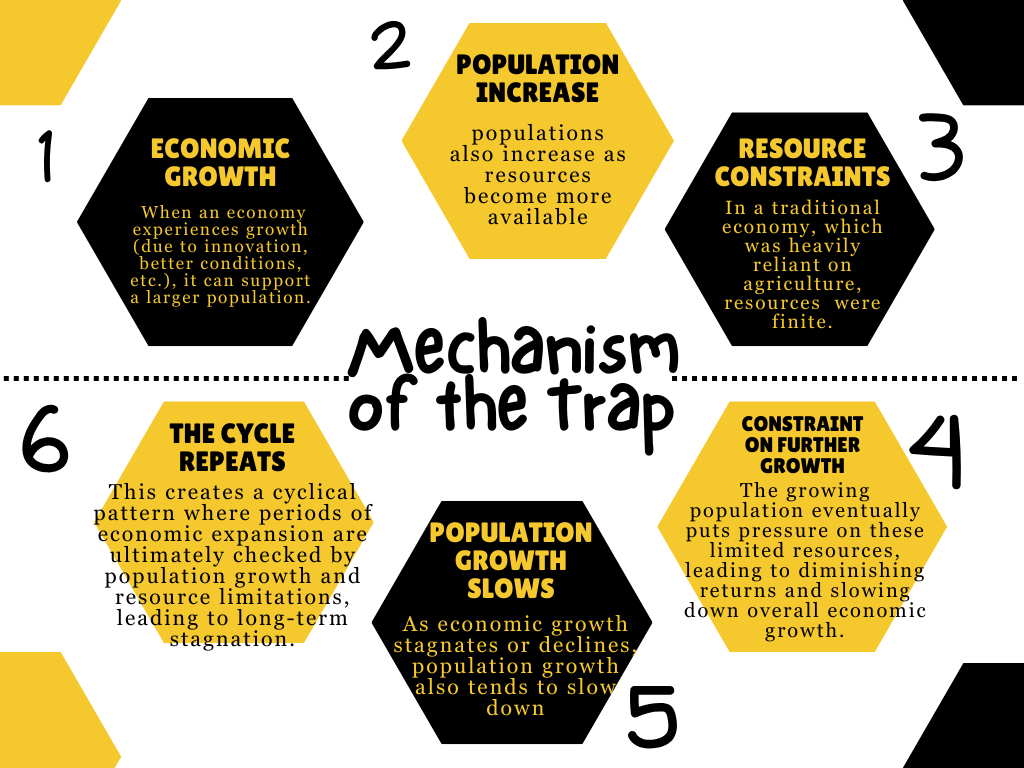

Malthusian Trap is a key explanation for the long-term economic stagnation observed in the traditional world:

-

Phases of Growth and Stagnation: The traditional economy likely experienced periods of faster economic growth followed by population increases and subsequent slowdowns in both economic and population growth.

-

The Inability to Escape: The Malthusian Trap essentially kept the overall economy from experiencing sustained, rapid growth because any gains were eventually offset by population increases straining the available resources.

The Great Divergence: The Hockey Stick of Economic Growth and the Role of Social Structure

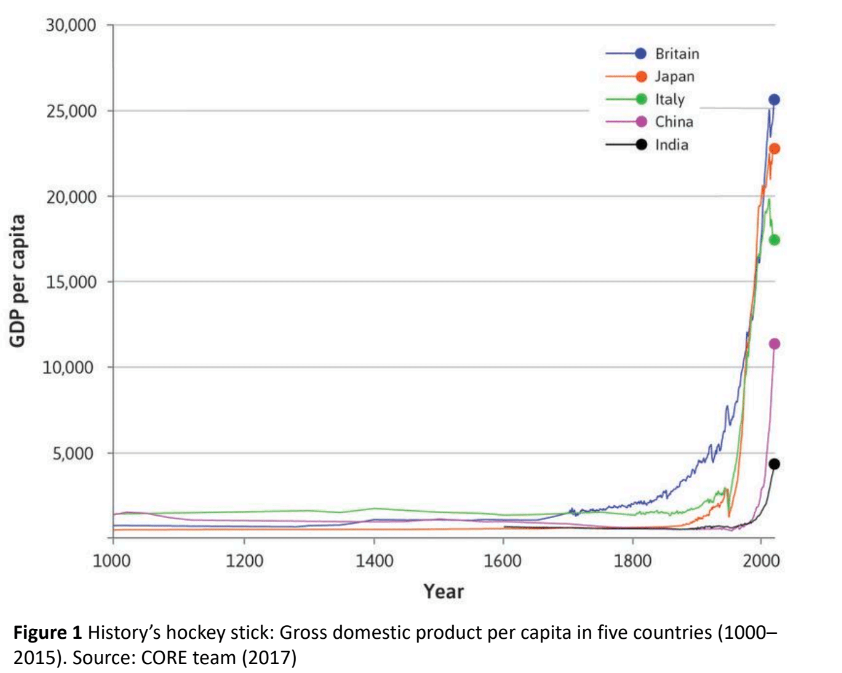

We'll now shift the focus to the dramatic economic transformation that occurred after the 1500s, particularly post-1750, leading to unprecedented and rapid economic growth, often referred to as the "hockey stick" phenomenon. We contrast this with the long period of stagnation in the traditional world.

The Uncharacteristic Exponential Growth

- The "Hockey Stick" Phenomenon: Above diagram illustrating that for millennia, per capita income remained largely stagnant and similar across different regions. However, starting around the 1700s, England experienced a sudden and rapid acceleration in per capita income, reaching levels significantly higher than other countries. This pattern of long stagnation followed by a sharp upward curve resembles a hockey stick.

- Global Spread of Rapid Growth: This "hockey stick" growth subsequently spread to other parts of Europe, the United States, Japan, and more recently, East Asia, including China and India.

- Modern Expectations of Growth: Today, we expect and desire high rates of economic growth (8-12% annually), a stark contrast to the historically slow pace of economic development. This expectation is a direct consequence of the uncharacteristic growth witnessed in recent centuries.

Debating the Causes of the "Hockey Stick"

The Role of Social Structure in Knowledge Transmission and Innovation: From Embeddedness to Markets

Let's now explore how the underlying social structure of a society significantly influences its capacity for innovation, knowledge transmission, and consequently, productivity growth. We'll use a thought experiment about educating a child in pre-modern times to illustrate the different models of learning and their implications.

A Thought Experiment: Educating a Child in the Pre-Modern Era

Three potential options for a parent in the 15th or 16th century seeking to educate their child:

1. Home-Based Learning:

- Method: The parent directly teaches the child.

- Benefit: Perfect alignment of incentives – the parent has the child's best interests at heart and will likely try their best to teach.

- Disadvantage: Limited scope of knowledge and skills – the child's learning is restricted by the parent's expertise and occupation, often leading to the child following the same profession.

2. Embedded Institutional Learning (Clan or Guild):

- Method: Sending the child to a teacher within the extended family (clan/caste) or to a guild master.

- Potential Advantage: The master likely possesses more specialized knowledge and skills compared to the parent.

- Potential Disadvantage: Misaligned incentives – the master's motivation to provide the absolute best education might be less than that of a parent.

- Mitigation through Social Structure: In an embedded environment where people know each other and reputations matter, parents can monitor the teacher and make informed decisions based on the teacher's standing within the community. This social structure helps mitigate the risk of poor instruction.

3. Market-Based Learning:

- Method: Sending the child to the best possible teacher, regardless of their social ties or location (within the city or even globally in the modern context).

- Theoretical Ideal: Learning from the most knowledgeable individuals should lead to the highest quality of education.

- Potential Pitfall: The best teachers might have a large number of students, potentially diluting the attention and resources available to each individual child.

- Theoretical Advantage (with Reliability): If a system could be created where anyone can learn from anyone else, overcoming the issue of unreliability and opportunism, it would theoretically be the most efficient way to learn and foster innovation and productivity growth.

The Theoretical Efficiency of Market-Based Exchange

We conclude that, theoretically, a market-based system of exchange – where individuals can learn from, partner with, and do business with strangers – has the potential to be the most efficient driver of learning, innovation, and economic growth. This is because it allows access to the widest pool of talent and expertise. However, the crucial caveat is the need to address the inherent challenges of unreliability and opportunism that arise when dealing with strangers, a topic explored in previous discussions regarding the necessity of contractual infrastructure and formalization.

No Comments