Traditional Business

The Ubiquity of Exchange with Strangers

Let's see The pervasive nature of our interactions with strangers in modern life:

- Food Delivery: Ordering from restaurants where the cooks and delivery personnel are unknown.

- Transportation: Taking taxis or using ride-sharing services with unfamiliar drivers.

- Commuting: Sharing public transport with a multitude of unknown individuals.

- Banking: Conducting transactions with bank tellers or staff we haven't met before.

- Retail: Shopping at grocery stores or other shops where interactions are primarily with unfamiliar staff.

This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in large, diverse cities like Bangalore, where innovations like Swiggy further expand our interactions with a wide array of unfamiliar service providers daily. In contrast, smaller towns often involve more frequent interactions within a familiar social circle.

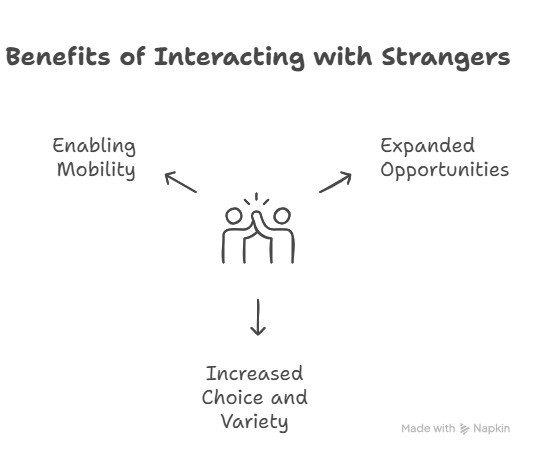

Why Does Interacting with Strangers Matter?

- Expanded Opportunities: Interacting with strangers significantly broadens the scope of available goods, services, and experiences. It unlocks a much larger "menu" of possibilities.

- Increased Choice and Variety: The ability to transact with a wider pool of individuals leads to greater choice and variety in what we can consume and experience.

- Enabling Mobility and New Experiences: For example, one can move to a completely new city for education or work, where everyone is initially a stranger, but through various interactions, familiarity develops. Contractual exchange underpins the ability to engage with these initially unfamiliar environments and build new connections.

The Fundamental Promise: Expanding Your Circle of Opportunity

The core advantage of contractual exchange, which allows us to interact with strangers, is the expansion of our opportunities. It breaks down the limitations imposed by relying solely on established relationships or power dynamics. By enabling transactions with individuals beyond our immediate social circles, contractual exchange unlocks a far wider range of possibilities for consumption, learning, and personal growth.

The Challenges and Persistence of Non-Contractual Exchange

The Prevalence of Relational and Power-Based Exchange

- Historical Norm: For most of human history, and even today in many parts of the world, people have primarily lived in smaller, more tightly knit communities.

- Limited Interaction with Strangers: In these settings, the majority of exchanges occur within established social circles, relying on relational exchange (based on personal connections, trust, and reputation) or power-based exchange (driven by authority and hierarchy).

- Contractual Exchange as an Exception: Exchange with strangers and the associated contractual exchange (based on formal agreements and legal frameworks) tend to be less common, existing in smaller "pockets."

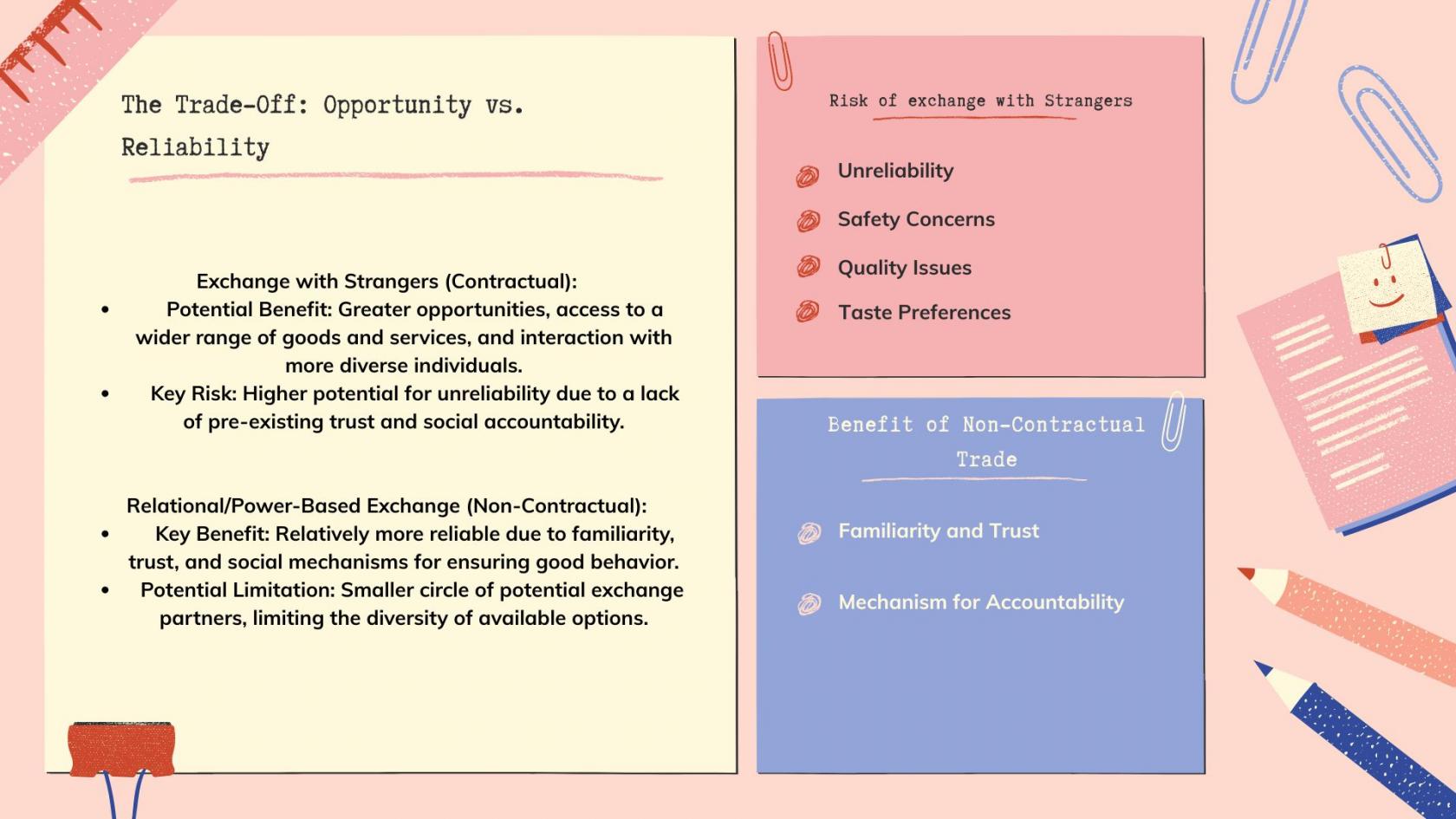

The Risks of Exchanging with Strangers

-

Unreliability: Strangers are inherently less predictable than known individuals. There's a greater chance of encountering issues like:

- Safety Concerns: As highlighted by the example of taking a taxi with a stranger.

- Quality Issues: Uncertainty about the standards of food prepared by an unknown person.

- Taste Preferences: Potential mismatch in expectations when dealing with unfamiliar providers.

The Preference for Reliable Non-Contractual Exchange

Due to these risks, people often prefer the perceived reliability of relational or power-based exchange, especially within embedded social structures:

-

Familiarity and Trust: When dealing with known individuals, there's a pre-existing level of trust and understanding based on past interactions and shared social context.

-

Mechanisms for Accountability: In relational exchange, if someone acts unreliably or cheats, there are social mechanisms to address this, ranging from direct reprimands to indirect forms of social ostracization or damage to reputation within the community. This provides a degree of informal enforcement.

The Stickiness of Relational and Power-Based Exchange

- Building Rapport and Tacit Knowledge: Repeated interactions lead to the development of personal connections (rapport) and shared, unwritten understandings (tacit knowledge). This includes specific communication styles and ways of working together that are unique to the individuals involved.

- Difficulty in Transferring Tacit Knowledge: This embedded tacit knowledge is hard to codify or transfer to new relationships with strangers, making it challenging to start anew.

- Comfort and Efficiency: Existing relationships offer ease of communication and exchange due to this shared understanding, making individuals less inclined to venture into the uncertainties of dealing with strangers.

- Persistence of Hierarchies: Similarly, in power-based exchange (like a command-style management), established hierarchies and patterns of authority are difficult to break down and replace with a system of equal, contractual interactions with unfamiliar parties.

The Historical Emergence of Impersonal Exchange

Early Cities as Hubs for Impersonal Exchange

- Urban Centers as Marketplaces: Cities historically arose in locations that facilitated trade and exchange between people from neighboring areas. Examples include the Mahajanapadas of ancient North India like Patliputra and Banaras, which served not only as administrative centers but also as crucial marketplaces.

- Ports and Trade Routes: Similarly, port cities naturally became hubs for impersonal exchange due to the influx of goods and traders from different regions.

- Limited Scope of Early Impersonal Exchange: However, the speaker notes that this early form of impersonal exchange was often limited in scope and nature.

Characteristics of Early Impersonal Exchange

- Transparent Products: Much of the trade involved goods with easily verifiable quality, such as basic commodities like rice. This reduced the risk of uncertainty regarding the product's value.

- Spot Transactions: Exchanges typically occurred on the spot with immediate cash payment. This eliminated the risk associated with credit transactions and the uncertainty of future payment.

- Minimizing Uncertainty: The combination of transparent goods and cash transactions aimed to minimize uncertainty in the exchange process.

The Challenge of Uncertain Exchanges

- Credit Transactions: Buying on credit introduces the risk of the buyer not repaying the borrowed amount, making the outcome of the exchange uncertain.

- Experience Goods: Products or services whose quality can only be assessed after consumption (experience goods) also involve uncertainty at the point of purchase.

The Shift in North Western Europe (Around the 16th Century)

A significant turning point occurred around the 16th century, particularly in North Western European cities like Amsterdam and London:

- Emergence of a Different Economic Model: A new type of economy began to develop, characterized by the creation of various institutions (both centralized and decentralized) designed to facilitate exchange with strangers on a larger scale and with greater ease.

- Systematic and Scaled Impersonal Exchange: While impersonal exchange existed earlier, this period marked the beginning of a more systematic and large-scale form of it.

No Comments