Capital gearing and theories of capital structure

What is the Capital Gearing Ratio?

The capital gearing ratio, also known as the debt-to-equity ratio, is a financial metric that indicates the proportion of a company's capital that comes from debt compared to its equity. Essentially, it shows how much a company relies on borrowed money (debt) versus its own funds (equity) to finance its operations and growth.

It's a way to measure a company's financial leverage.

Formula:

The most common way to calculate the capital gearing ratio is: Capital Gearing Ratio = Total Debt / Total Equity

Where:

- Total Debt: This typically includes all interest-bearing liabilities such as loans, bonds, and other forms of borrowing.

- Total Equity: This represents the total value of the company owned by its shareholders. It includes common stock, preferred stock, and retained earnings.

Key Idea:

- A high gearing ratio means a company relies more on debt financing.

- A low gearing ratio means a company relies more on equity financing.

Understanding High vs. Low Gearing

Here's a simple breakdown:

High Gearing (High Debt-to-Equity Ratio):

-

Pros:

- Potentially higher returns: If a company earns a higher return on its assets than the interest rate it pays on debt, the extra profit goes to shareholders, magnifying their returns (called financial leverage).

- Tax advantage: Interest payments on debt are often tax-deductible, reducing the company's tax burden.

-

Cons:

- Higher financial risk: If the company doesn't generate enough profit to cover its interest payments, it could face financial difficulties or even bankruptcy.

- Less flexibility: High debt levels can limit a company's ability to take on new opportunities or weather economic downturns.

Low Gearing (Low Debt-to-Equity Ratio):

-

Pros:

- Lower financial risk: The company is less vulnerable to interest rate fluctuations or economic slowdowns.

- More financial flexibility: The company has more options for future borrowing or taking on new projects.

-

Cons:

- Potentially lower returns: If the company is very profitable, using less debt means that the benefits of financial leverage are missed.

- Higher cost of capital: Equity is generally more expensive than debt, so relying heavily on equity can lead to a higher overall cost of capital.

Analogy:

Imagine two people buying a house:

- Person A takes out a large mortgage and a small down payment (high gearing). If house value goes up, person A gains more. However, if the house price falls, Person A faces more risk because they must still pay the mortgage.

- Person B makes a large down payment with little mortgage (low gearing). This is less risky but they gain less when house value goes up.

Why is the Capital Gearing Ratio Important?

- Risk Assessment: It helps investors assess the financial risk associated with a company. A high ratio indicates higher risk.

- Financial Planning: It helps company management determine the appropriate mix of debt and equity financing for their business.

- Benchmarking: It allows investors to compare the capital structure of different companies within the same industry.

- Lending Decisions: Lenders use this ratio to evaluate the creditworthiness of companies before approving loans.

What is a "Good" Gearing Ratio?

There isn't a universally "good" gearing ratio. It depends on:

- Industry: Capital-intensive industries often have higher gearing ratios than those with lower fixed costs.

- Company Maturity: Young and growing companies often rely less on debt, while established companies can handle more debt.

- Economic Conditions: In times of economic prosperity, companies can handle more debt, while during recessions, debt can be more problematic.

- Management Strategy: Some companies have a preference for a higher degree of leverage, while others take a more conservative approach.

Generally:

- A ratio of around 1 or below is considered low to moderate.

- A ratio above 2 is usually considered high (but may be normal in some capital-intensive sectors).

Theories of Capital Structure:

The Basics of Capital Structure

Before we discuss theories, it's important to understand what capital structure actually is. In essence, it's the specific combination of debt and equity a company uses to fund its operations. Debt refers to borrowed money that needs to be repaid, like loans and bonds, while equity is the money invested by shareholders who own a piece of the company. The decision of how much debt and how much equity to use is crucial because it can significantly impact a company's overall value and financial health. Different theories attempt to explain what the best combination of debt and equity might be for any given firm.

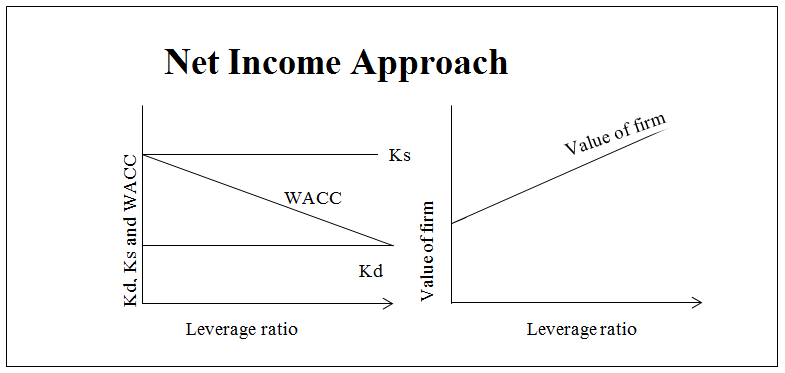

1. Net Income Approach

One of the simplest, but ultimately flawed, ideas is the Net Income (NI) approach. This theory suggests that a company can maximize its value simply by using as much debt as possible. The logic here is based on the idea that debt is always cheaper than equity. Because interest payments on debt are typically lower than the returns expected by equity investors, this theory implies that substituting equity for debt will continuously reduce the company's overall cost of capital. While it's true that debt often appears cheaper at first glance, the NI approach fails to consider that excessive debt increases a company's financial risk. The increased risk will result in increased costs of both debts and equity, making this theory unsuitable for the real world.

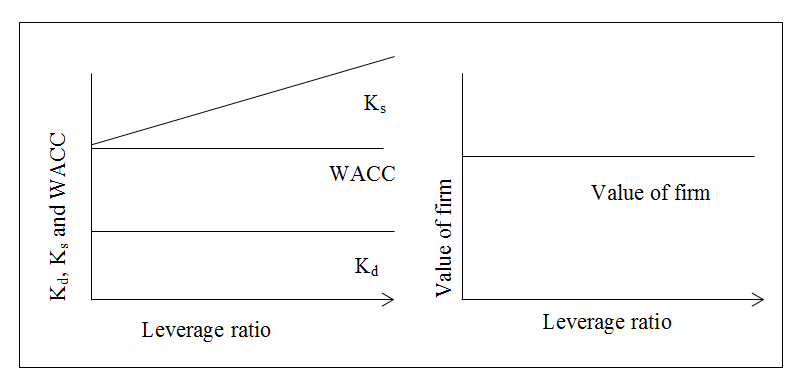

2. Net Operating Income Approach

Another early theory, the Net Operating Income (NOI) approach, presents a contrasting viewpoint. Unlike the NI approach, this theory argues that a company's value remains constant regardless of its capital structure. The logic is that a company's overall cost of capital remains the same no matter the mix of debt and equity. If a company uses more debt, shareholders will demand a higher return to compensate for increased risk, and vice versa. This increase of required return from shareholders cancels out any apparent advantage of using cheaper debt. Thus, the NOI approach concludes that there is no optimal level of debt, and any combination of debt and equity will have no net effect on the total value of the company. However, this approach falls short by ignoring the effects of taxes and financial distress costs in the real world.

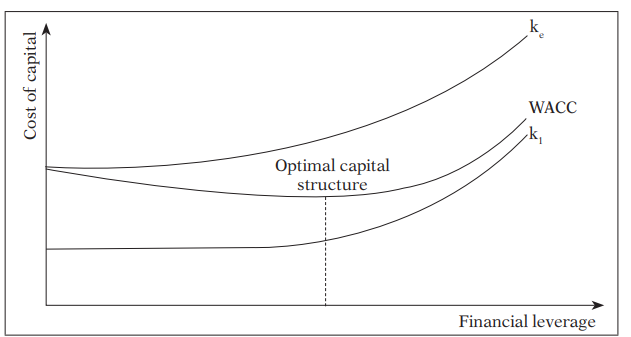

3. Traditional Approach

A more practical perspective is offered by the traditional approach. This theory acknowledges that there is indeed an optimal capital structure, one that achieves a balance between the advantages of debt and its risks. It suggests that initially, using more debt can lower a company's cost of capital due to the tax advantage of interest payments (they are often tax-deductible). As the company continues to add debt, the financial risk rises, and the cost of debt and equity begins to increase. At a certain point, the increased risk outweighs the tax benefits, and the company's overall cost of capital will start to increase, decreasing its overall value. The traditional approach believes there is an ideal mix of debt and equity that minimizes the cost of capital, which maximizes the value of the firm.

4. The Modigliani-Miller (MM) Theorem:

The Modigliani-Miller (MM) theorem is another cornerstone in capital structure theory. It initially proposes, in an idealized world with no taxes, no transaction costs, and no bankruptcy costs, that a company's capital structure is entirely irrelevant. In this world, the way a company finances itself has absolutely no impact on its total value. Changes in the debt levels will only cause a corresponding change in the risk and return for the equity investors, resulting in no net effect. While clearly not applicable in the real world, this simple version of the MM theorem is a starting point for understanding capital structure. When taxes are introduced to the model, the MM theorem argues that debt becomes beneficial because interest expense is tax deductible, increasing the total value of the company. However, like other theories, this version of MM ignores the risk of financial distress. The most complex but practical version of MM acknowledges that there are costs associated with financial distress, such as the risk of bankruptcy. It suggests that companies should aim for a level of debt that balances the tax benefits against the increased probability of financial distress, often called the trade-off theory.

5. The Pecking Order Theory

The pecking order theory offers a different perspective, focusing on how companies actually make financing decisions, rather than aiming to find an optimal mix of debt and equity. It suggests that companies have a specific preference when choosing where to get their funds. They would first use retained earnings (profits) because this involves less external scrutiny, then debt, and finally, they will opt for issuing new equity. The reasoning behind this preference is information asymmetry: management usually knows more about the company's actual value than outside investors. So, management may hesitate to issue new equity because it can signal that the management thinks the stock price is overvalued, thus negatively affecting its value. This theory offers an explanation for why companies often favor internal financing and avoid issuing new shares unless absolutely necessary.

No Comments